The New Chevalier Sonata (c. 1778-80)

The Story of the Source Piece, continued...

Following on from the matters raised in Composer’s Notes – Section 1, which can be found at the beginning of the piano score, there are important questions to be answered about the source piece – Le Sonate pour la Harpe, avec accompagnement de Flute:

· When was it written?

· For whom was it written?

· Why is it so unbalanced away from the flute, in favour of the harp?

· Why was it unpublished, when so many of his other works found a publisher?

Composer’s Notes – Section 1 covers the likely date of composition (1778-1780).

I surmise that the piece was composed for Queen Marie Antoinette, Chevalier's patron, who played the harp.

Regarding the disparity between the instruments, the flute part veers between equality, doubling, and extended silences, in contrast with the leading harp part. Setting aside, for the moment, musical reasons for doing something like this, the disparity makes a great deal of sociological sense, in the context of the fact that the Queen took precedence over every single person in the country, other than her husband: and that precedence needed to be honoured at all times. Therefore, inequality between the parts was a desirable measure, in a culture wherein demarcation of social strata was minutely observed.

Regarding the flute part, Bologne himself did not play that instrument. He would have had to engage a member of his orchestra – or even Mozart’s duke – to play the subordinate flute part. Whoever played it would have been Marie Antoinette's social inferior, regardless of his absolute social position.

The Story of the Source Piece, continued...

Following on from the matters raised in Composer’s Notes – Section 1, which can be found at the beginning of the piano score, there are important questions to be answered about the source piece – Le Sonate pour la Harpe, avec accompagnement de Flute:

· When was it written?

· For whom was it written?

· Why is it so unbalanced away from the flute, in favour of the harp?

· Why was it unpublished, when so many of his other works found a publisher?

Composer’s Notes – Section 1 covers the likely date of composition (1778-1780).

I surmise that the piece was composed for Queen Marie Antoinette, Chevalier's patron, who played the harp.

Regarding the disparity between the instruments, the flute part veers between equality, doubling, and extended silences, in contrast with the leading harp part. Setting aside, for the moment, musical reasons for doing something like this, the disparity makes a great deal of sociological sense, in the context of the fact that the Queen took precedence over every single person in the country, other than her husband: and that precedence needed to be honoured at all times. Therefore, inequality between the parts was a desirable measure, in a culture wherein demarcation of social strata was minutely observed.

Regarding the flute part, Bologne himself did not play that instrument. He would have had to engage a member of his orchestra – or even Mozart’s duke – to play the subordinate flute part. Whoever played it would have been Marie Antoinette's social inferior, regardless of his absolute social position.

|

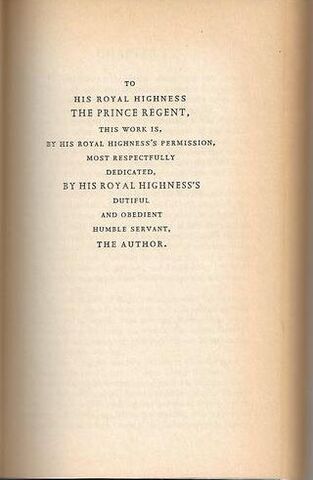

One question that arises for me, concerns the fact that, if Saint-Georges did indeed compose the piece for Marie Antoinette, why there is no dedication to her on the score? Take, for example, the dedication that Jane Austen was forced to write for the Prince Regent at the beginning of Emma. He lobbied for this: she did not offer it of her own will, because she strongly disapproved of him. However, if a member of the Royal Family wanted a dedication, he got it, regardless of the author’s personal feelings. Saint-George and Marie Antoinette got on well, though: so one would expect to see a dedication there, had the piece been presented to her.

One potential answer to this question would be that Bologne did so in a letter that accompanied the score, which was subsequently lost, in the revolutionary upheaval. |

Here is another question! If the piece was written for the queen, was she actually good enough to play it? The harp part does not seem particularly easy to me. It is in Eb major; but the queen had only been learning for four years. Even after much practice - for which she was well-known, I understand - surely it would still have been a challenge for her? Perhaps Saint-Georges went with the flow in the composition process, and then realised that he had composed something too difficult for her? That would have been deeply problematic – and could have cost him his favour at court. That would explain why he may never have handed the piece over to her – and why it therefore lacks a formal dedication to his patroness.

Unlike most of the music he composed in the 1770s (his richest compositional time), Saint-George’s Sonate went unpublished. I have two hypotheses about this. The first is that the piece may have been composed too close to the 1780s, when he moved into a greater level of political awareness and involvement. This took him away from his music - and abroad - for some years. It’s entirely possible that he lacked time to arrange a publisher before he left France.

The second hypothesis is that Saint-Georges did submit it to a publisher, but that the publisher thought that there wouldn’t be a big enough market for the piece, and thus refused to take it on. That is possible, bearing in mind how new (and unusual) the flute & harp combination was.

As stated in Composer’s Notes – Section 1, I have settled upon c.1779 as the date of composition of this work. In addition to the arguments outlined above, I have always regarded the Sonate as an example of ancien régime aristocratic salon music, which came to a halt after the Revolution. I have not yet referred to any published monographs on the topic, but hope to do so. My research, so far, has been carried out exclusively via the internet. If I do come across information which expands upon – or contradicts – my surmises here, I will be able to update this page accordingly. Hence I have decided to publish these notes via my website.

Unlike most of the music he composed in the 1770s (his richest compositional time), Saint-George’s Sonate went unpublished. I have two hypotheses about this. The first is that the piece may have been composed too close to the 1780s, when he moved into a greater level of political awareness and involvement. This took him away from his music - and abroad - for some years. It’s entirely possible that he lacked time to arrange a publisher before he left France.

The second hypothesis is that Saint-Georges did submit it to a publisher, but that the publisher thought that there wouldn’t be a big enough market for the piece, and thus refused to take it on. That is possible, bearing in mind how new (and unusual) the flute & harp combination was.

As stated in Composer’s Notes – Section 1, I have settled upon c.1779 as the date of composition of this work. In addition to the arguments outlined above, I have always regarded the Sonate as an example of ancien régime aristocratic salon music, which came to a halt after the Revolution. I have not yet referred to any published monographs on the topic, but hope to do so. My research, so far, has been carried out exclusively via the internet. If I do come across information which expands upon – or contradicts – my surmises here, I will be able to update this page accordingly. Hence I have decided to publish these notes via my website.

Principal Compositional & Improvement Strategies

Noteworthy Interventions

Please note that the notes below refer to the original key of composition only, which is Eb major - at the start and finish of each movement.

Andante

bb.9-14 onwards – harp figures simplified in pf RH (also in recapitulation)

bb. 9 & 10 - inconsistent bass note lengths evened out to crotchets (quarter notes)

b.21 thirds/sixths inserted to harmonise between solo instrument (oboe, for short) & pf RH, instead of parallel octaves between flute & harp. Also in the recapitulation.

b.28 - Key signature changed to the dominant major, in order to reduce the use of natural signs for the ‘A’s – almost all of which were missing from the original, in any case

b.31, beat 2 - First major re-voicing. The treble harp line is transferred primarily to the oboe, until b. 50. During this stretch, harmonising crotchets have been inserted into the pf RH, to create a consistent three part texture. This was necessary, as the oboe was originally tacet during almost the entire section, leaving only two lines for much of it.

Recap. ornamentation written in to the melody line at the end, for cadential emphasis.

Tempo Minuetto

Bar 7 - Accidental adjustment (see extensive notes)

On the original manuscript (MS), the first semiquaver (1/16th-note) in the melody line is an A. The key signature renders it – by default - as an Ab, but the tonality of the preceding b.6 – which contains Dominant (Bb major) harmonies throughout – and the cadential progression through b. 7 – make it clear that this should be an A natural. B.8 completes the modulation into the Dominant, so that the piece – having commenced in Eb major, is now firmly established in Bb major. In the bass line, the Eb at the beginning of b.7 should be regarded as a V7c chord in Bb major – i.e. an F-major 7th chord with the notes F - A natural – C – Eb: not as any other chord.

MS: the only ‘A’ in the bar is this initial semiquaver. In the last beat (an implied F major chord), Bologne places the flute and harp one fifth apart, but without a harmonizing third (an A natural). Therefore, not only does the use of an Ab at the beginning of the bar suggest a chromaticism foreign to Bologne’s use of common practice tonality at the time, it leaves the bar without a corrective A natural, at any point. Playing an Ab at the beginning of this bar leaves it without a leading note into Bb major. Any decent publisher would have challenged this: but this piece was not set before a publisher. It is an unpublished manuscript.

N.B. My arrangement adds an A natural to the piano harmonies in the final beat of b.7.

Two things are vital to note:

Firstly, that the entire original MS is heavily error-strewn, displaying only a moderate level of Theoretical understanding; and an apparent lack of editorial intervention from a colleague or publisher. This supposition fits with Bologne’s life story, which would have led to notational shortcomings in comparison with a composer like Mozart, whose father was an accomplished musician, and taught him correct notation from an early age.

In the Andante, ‘A natural’ after ‘A natural’ is missing, particularly in the B section – which has modulated into Bb major. This is partly because a key change was not inserted at b.28 in the original manuscript. Therefore, an editor has to make a judgment call about any anomalous or strange-sounding notes, throughout the work, and keep in mind the notational shortcomings of the Andante, in this same key (Bb major).

Secondly, returning to Tempo Minuetto, in b.9, both flute and harp unison melody lines lack an accidental (in this case, a flat sign) in front of the third note, a ‘D’. The Bb minor tonality is established in b.10, modulating to F minor in b. 12. Therefore, all performers I have heard change the ‘D natural’ in b.9 to a Db, in anticipation of the next bar, but many fail to change the Ab in b.7 to an A natural – an odd omission, bearing in mind how out-of-place the Ab sounds.

The final reason for my choice of A natural in b.7 is the harmonic rhythm that Bologne establishes at the beginning of this piece. Bb.1&2 and bb.5&6 have one chord throughout, whereas bb. 3&4 have two. That implies that b.7 should have two chords in it, not three (which would be the case, if the chord on beat 1 were harmonized as anything other than F7c.) B.8 has only one chord, as it comes to rest in Bb major, at the end of the first 8-bar section.

Antiphony - for breathing reasons

bb. 23 & 24 Missing bass line completed, in accordance with normal rules of harmony for this historical period

b.25 Flute material antiphonally re-allocated to the piano, in order to create breathing space after the initial, repeated A & B sections. Also - in recapitulation.

Some repositioning in the solo line during passage work later on in the movement, depending upon instrument (i.e. Saxophone) (up/down octave, etc.)

Cadenza material - transfer & redistribution between all three parts, for reasons of common practice logic & breathing

Rondeau

b.9 onwards – pf RH - unison doubling removed, and changed to harmonisation in 3rds

b.11 Bass line adjustment – first note now in root position (Bb from D), to accommodate inserted pf RH harmony

b.18 onwards – last beat, pf RH dropped one octave

b. 20 last beat – pf RH changed to harmonisation in 3rds

bb.23-26 pf RH insertion: harmony in 3rds

bb.37-39 insertion of descending pf LH bass minims to create a two-part texture

b. 41 Initial bass note changed to root position (F from A)

bb.41-44 pf RH harmony insertion

bb. 49-51 restatement of inserted bass part from bb. 37-39

b. 52 Bb inserted pf LH

Antiphonal redistribution of much of the harp treble writing, throughout much of B section

Ossia created to help pianist to navigate awkward harp figure, and to give options as to whether to play an E natural or E flat in this passage, as Saint-Georges uses both, sequentially (and in error), in the original

bb. 57-60 pf RH harmonies written in

Cadenza reassigned from harp to oboe

‘D’ divided between two octaves in the oboe cadenza, in order to create a rhythmically-cohesive sequence of notes

- The establishment of consistency of texture (predominantly three parts) throughout the piece

- The establishment of melodic balance between the instruments

- The utilisation of antiphony (first employed by Saint-Georges in bb. 16-18) when redistributing the lines.

Noteworthy Interventions

Please note that the notes below refer to the original key of composition only, which is Eb major - at the start and finish of each movement.

Andante

bb.9-14 onwards – harp figures simplified in pf RH (also in recapitulation)

bb. 9 & 10 - inconsistent bass note lengths evened out to crotchets (quarter notes)

b.21 thirds/sixths inserted to harmonise between solo instrument (oboe, for short) & pf RH, instead of parallel octaves between flute & harp. Also in the recapitulation.

b.28 - Key signature changed to the dominant major, in order to reduce the use of natural signs for the ‘A’s – almost all of which were missing from the original, in any case

b.31, beat 2 - First major re-voicing. The treble harp line is transferred primarily to the oboe, until b. 50. During this stretch, harmonising crotchets have been inserted into the pf RH, to create a consistent three part texture. This was necessary, as the oboe was originally tacet during almost the entire section, leaving only two lines for much of it.

Recap. ornamentation written in to the melody line at the end, for cadential emphasis.

Tempo Minuetto

Bar 7 - Accidental adjustment (see extensive notes)

On the original manuscript (MS), the first semiquaver (1/16th-note) in the melody line is an A. The key signature renders it – by default - as an Ab, but the tonality of the preceding b.6 – which contains Dominant (Bb major) harmonies throughout – and the cadential progression through b. 7 – make it clear that this should be an A natural. B.8 completes the modulation into the Dominant, so that the piece – having commenced in Eb major, is now firmly established in Bb major. In the bass line, the Eb at the beginning of b.7 should be regarded as a V7c chord in Bb major – i.e. an F-major 7th chord with the notes F - A natural – C – Eb: not as any other chord.

MS: the only ‘A’ in the bar is this initial semiquaver. In the last beat (an implied F major chord), Bologne places the flute and harp one fifth apart, but without a harmonizing third (an A natural). Therefore, not only does the use of an Ab at the beginning of the bar suggest a chromaticism foreign to Bologne’s use of common practice tonality at the time, it leaves the bar without a corrective A natural, at any point. Playing an Ab at the beginning of this bar leaves it without a leading note into Bb major. Any decent publisher would have challenged this: but this piece was not set before a publisher. It is an unpublished manuscript.

N.B. My arrangement adds an A natural to the piano harmonies in the final beat of b.7.

Two things are vital to note:

Firstly, that the entire original MS is heavily error-strewn, displaying only a moderate level of Theoretical understanding; and an apparent lack of editorial intervention from a colleague or publisher. This supposition fits with Bologne’s life story, which would have led to notational shortcomings in comparison with a composer like Mozart, whose father was an accomplished musician, and taught him correct notation from an early age.

In the Andante, ‘A natural’ after ‘A natural’ is missing, particularly in the B section – which has modulated into Bb major. This is partly because a key change was not inserted at b.28 in the original manuscript. Therefore, an editor has to make a judgment call about any anomalous or strange-sounding notes, throughout the work, and keep in mind the notational shortcomings of the Andante, in this same key (Bb major).

Secondly, returning to Tempo Minuetto, in b.9, both flute and harp unison melody lines lack an accidental (in this case, a flat sign) in front of the third note, a ‘D’. The Bb minor tonality is established in b.10, modulating to F minor in b. 12. Therefore, all performers I have heard change the ‘D natural’ in b.9 to a Db, in anticipation of the next bar, but many fail to change the Ab in b.7 to an A natural – an odd omission, bearing in mind how out-of-place the Ab sounds.

The final reason for my choice of A natural in b.7 is the harmonic rhythm that Bologne establishes at the beginning of this piece. Bb.1&2 and bb.5&6 have one chord throughout, whereas bb. 3&4 have two. That implies that b.7 should have two chords in it, not three (which would be the case, if the chord on beat 1 were harmonized as anything other than F7c.) B.8 has only one chord, as it comes to rest in Bb major, at the end of the first 8-bar section.

Antiphony - for breathing reasons

bb. 23 & 24 Missing bass line completed, in accordance with normal rules of harmony for this historical period

b.25 Flute material antiphonally re-allocated to the piano, in order to create breathing space after the initial, repeated A & B sections. Also - in recapitulation.

Some repositioning in the solo line during passage work later on in the movement, depending upon instrument (i.e. Saxophone) (up/down octave, etc.)

Cadenza material - transfer & redistribution between all three parts, for reasons of common practice logic & breathing

Rondeau

b.9 onwards – pf RH - unison doubling removed, and changed to harmonisation in 3rds

b.11 Bass line adjustment – first note now in root position (Bb from D), to accommodate inserted pf RH harmony

b.18 onwards – last beat, pf RH dropped one octave

b. 20 last beat – pf RH changed to harmonisation in 3rds

bb.23-26 pf RH insertion: harmony in 3rds

bb.37-39 insertion of descending pf LH bass minims to create a two-part texture

b. 41 Initial bass note changed to root position (F from A)

bb.41-44 pf RH harmony insertion

bb. 49-51 restatement of inserted bass part from bb. 37-39

b. 52 Bb inserted pf LH

Antiphonal redistribution of much of the harp treble writing, throughout much of B section

Ossia created to help pianist to navigate awkward harp figure, and to give options as to whether to play an E natural or E flat in this passage, as Saint-Georges uses both, sequentially (and in error), in the original

bb. 57-60 pf RH harmonies written in

Cadenza reassigned from harp to oboe

‘D’ divided between two octaves in the oboe cadenza, in order to create a rhythmically-cohesive sequence of notes

Dynamics

There are NO dynamics in either part, in the original MS. Therefore, all dynamics are editorial.

Cadenzas

All cadenzas were written for the harp. The flute cadenza in the recap. of the Andante (b. 65) is simply marked with a pause, in the original MS. I filled it in with a broken chord figure taken from the harp cadenza at the end of the B section (b. 50)

Articulation

This is the most problematic area for discussion: a flashpoint issue. The big question was: what – and how much of it - to put onto the score? There are only a small number of original slurs and staccato markings on the MS – and some of these are inconsistent, inasmuch as a phrase of music may be articulated differently when it recurs later in the movement.

It is my supposition – as a composer – that the articulation markings on the MS were made by Saint-Georges in the process of composition: when his principal concern was the basic construction of the piece, rather than consideration of detail. The MS seems unedited by him or anyone else, which makes it problematic to treat it as an Urtext-like finished product with 'biblical' authority. If he – or a contemporaneous editor – had edited the piece, the articulations would most likely have been changed, in a number of places.

The articulations in the Saxophone score are heavily didactic, at the request of Professor Melanie Henry, who wanted saxophonists to be given clear stylistic guidance, in accordance with the practices outlined in treatises such as Quantz’s On Playing the Flute, for example.

The articulations in the other scores are less didactic; sometimes offer the performer different options; and are mostly in line with standard period instrument practice. My final decision was to decide to put sufficient markings onto the score as to be able to teach the correct style to someone unfamiliar with performing music of this period (i.e. an upper grade-level pupil); but not so many as completely to irritate a professional, who doesn't need to be told what to do. For that reason, sim. is used frequently, to keep the score clear of markings in places; and alternative articulations are given in others, such as Andante b.19 (melody line).

I advise anyone who wishes to study Saint-George's original articulations, to refer to the MS on IMSLP. Otherwise, I advise performers either to follow the suggestions on the score – if new to playing music from the period in a stylistic manner – or, if one is an experienced professional musician – simply to do one’s own thing. The issue of ‘original articulation’ should not be taken too seriously with this particular unrevised and unpublished score. Just do what you normally do, when playing a piece of this period – or what you think sounds good. That would be my recommended approach for professionals.

Acknowledgments - in Full

I thank Rosie Cousins of ABRSM, who gave great assistance with preparing the Andante score for publication in the abridged version for Grade 5 Saxophone. I understand that it was she who requested the simplification of the treble harp figure in bb.9-15. That has been a highly-important improvement to first entry of the melody instrument: creating a sense of serenity, rather than busy-ness. I have carried this improvement over into the New Chevalier Sonata version of the piece, and I am very grateful for her wisdom in this matter.

I also thank Melanie Henry - both in her role as Saxophone syllabus consultant for ABRSM, and as Professor of Saxophone at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music & Dance in London - for all her advice and suggestions about various issues relating to the Saxophone score, including articulation. Not only did she work with us on the Grade 5 Andante arrangement, but she also reviewed the entire professional version of the score (The New Chevalier Sonata); and kindly facilitated the British premiere in June 2022, at Trinity Laban. The work was performed by three talented student saxophonists, who played one movement each – with great aplomb.

I thank Sarah Roper, Solo oboist & Principal Oboe of the Real Orquesta Sinfónica de Sevilla for her wise request that the cadenza in the Rondeau be transferred from the piano (where I had left it) to the oboe; and for her willingness to engage deeply with issues of articulation, which was something for which I had very little energy, after all my construction work on the piece.

I also thank Katherine Needleman – Solo oboist & Principal Oboe of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra - for her crucial observations about Saint-Georges’ part-writing; and for her rigorous assessment of remaining weaknesses in the Rondeau’s piano part, which gave me the courage to change some bass notes into root position where required. I had been very reluctant to do this, owing to my desire to retain the original bass line unchanged throughout the piece. However, it was something that needed to be done. It was also in response to her piano play-throughs and comments about the awkwardness of bb.49-56, that I created the piano ossia section.

There are NO dynamics in either part, in the original MS. Therefore, all dynamics are editorial.

Cadenzas

All cadenzas were written for the harp. The flute cadenza in the recap. of the Andante (b. 65) is simply marked with a pause, in the original MS. I filled it in with a broken chord figure taken from the harp cadenza at the end of the B section (b. 50)

Articulation

This is the most problematic area for discussion: a flashpoint issue. The big question was: what – and how much of it - to put onto the score? There are only a small number of original slurs and staccato markings on the MS – and some of these are inconsistent, inasmuch as a phrase of music may be articulated differently when it recurs later in the movement.

It is my supposition – as a composer – that the articulation markings on the MS were made by Saint-Georges in the process of composition: when his principal concern was the basic construction of the piece, rather than consideration of detail. The MS seems unedited by him or anyone else, which makes it problematic to treat it as an Urtext-like finished product with 'biblical' authority. If he – or a contemporaneous editor – had edited the piece, the articulations would most likely have been changed, in a number of places.

The articulations in the Saxophone score are heavily didactic, at the request of Professor Melanie Henry, who wanted saxophonists to be given clear stylistic guidance, in accordance with the practices outlined in treatises such as Quantz’s On Playing the Flute, for example.

The articulations in the other scores are less didactic; sometimes offer the performer different options; and are mostly in line with standard period instrument practice. My final decision was to decide to put sufficient markings onto the score as to be able to teach the correct style to someone unfamiliar with performing music of this period (i.e. an upper grade-level pupil); but not so many as completely to irritate a professional, who doesn't need to be told what to do. For that reason, sim. is used frequently, to keep the score clear of markings in places; and alternative articulations are given in others, such as Andante b.19 (melody line).

I advise anyone who wishes to study Saint-George's original articulations, to refer to the MS on IMSLP. Otherwise, I advise performers either to follow the suggestions on the score – if new to playing music from the period in a stylistic manner – or, if one is an experienced professional musician – simply to do one’s own thing. The issue of ‘original articulation’ should not be taken too seriously with this particular unrevised and unpublished score. Just do what you normally do, when playing a piece of this period – or what you think sounds good. That would be my recommended approach for professionals.

Acknowledgments - in Full

I thank Rosie Cousins of ABRSM, who gave great assistance with preparing the Andante score for publication in the abridged version for Grade 5 Saxophone. I understand that it was she who requested the simplification of the treble harp figure in bb.9-15. That has been a highly-important improvement to first entry of the melody instrument: creating a sense of serenity, rather than busy-ness. I have carried this improvement over into the New Chevalier Sonata version of the piece, and I am very grateful for her wisdom in this matter.

I also thank Melanie Henry - both in her role as Saxophone syllabus consultant for ABRSM, and as Professor of Saxophone at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music & Dance in London - for all her advice and suggestions about various issues relating to the Saxophone score, including articulation. Not only did she work with us on the Grade 5 Andante arrangement, but she also reviewed the entire professional version of the score (The New Chevalier Sonata); and kindly facilitated the British premiere in June 2022, at Trinity Laban. The work was performed by three talented student saxophonists, who played one movement each – with great aplomb.

I thank Sarah Roper, Solo oboist & Principal Oboe of the Real Orquesta Sinfónica de Sevilla for her wise request that the cadenza in the Rondeau be transferred from the piano (where I had left it) to the oboe; and for her willingness to engage deeply with issues of articulation, which was something for which I had very little energy, after all my construction work on the piece.

I also thank Katherine Needleman – Solo oboist & Principal Oboe of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra - for her crucial observations about Saint-Georges’ part-writing; and for her rigorous assessment of remaining weaknesses in the Rondeau’s piano part, which gave me the courage to change some bass notes into root position where required. I had been very reluctant to do this, owing to my desire to retain the original bass line unchanged throughout the piece. However, it was something that needed to be done. It was also in response to her piano play-throughs and comments about the awkwardness of bb.49-56, that I created the piano ossia section.